The Royal Opera ©2025 Marc Brenner

The Royal Opera ©2025 Marc Brenner

Based on Prosper Mérimée’s eponymous novella, Georges Bizet’s Carmen of 1875, with a libretto by Ludovic Halévy and Henri Meilhac, is the story of the ultimate temptress. A gypsy and cigarette factory worker in Seville, Carmen has the power to entice any man she chooses. Once, however, they are besotted with her she quickly moves on, leaving them heart broken and unable to accept what has happened.

In the opera Don José, an army corporal, has almost everything he could ever desire. He has the sweet, loving Micaëla who is more than willing to marry him, a job he is proud of, and every opportunity to remain close, both physically and metaphorically, to his mother and home village. When Carmen decides that she likes him, however, he ends up sacrificing everything he has for her, and cannot accept it when she loses interest in him and turns to the torero, Escamillo.

If Carmen hardly sounds a sympathetic character, she can certainly engage an audience with her allure and steadfast determination to live by her own rules. Freedom is the most important thing to her so that when Don José threatens to kill her unless she says that she loves him, she accepts her fate, preferring death to proclaiming a lie and feeling a sense of imprisonment.

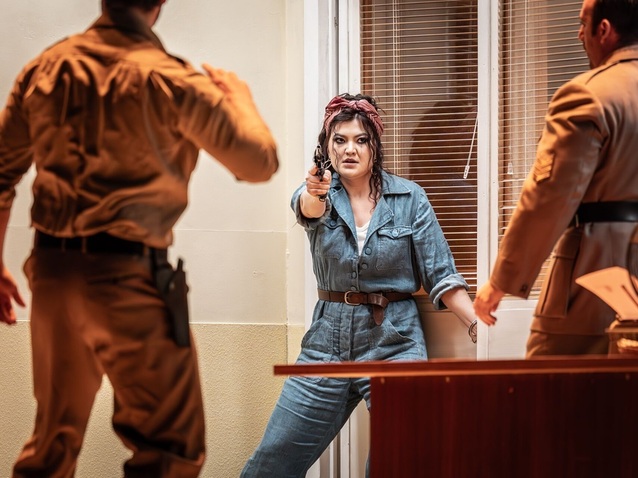

Damiano Michieletto's production of Bizet's Carmen, The Royal Opera ©2025 Marc Brenner

Damiano Michieletto’s staging for the Royal Ballet and Opera, which represents a co-production with Madrid’s Teatro Real and the Teatro alla Scala in Milan and is revived on this occasion by Dan Dooner, returns to Covent Garden having premiered there last year. He sets the action in the 1970s or thereabouts, and by moving the action forward to a relatively recent time, he aims to make the story relatable without destroying the notion of a traditional, close knit community. He also ensures, with designer Paolo Fantin, that each set comprises a vast open space and a smaller enclosed one, so that Act I features an officers’ hut within a larger town square.

The techniques Michieletto employs to convey ‘a “wild west”, where children wear cowboy hats and play with toy guns, and lawfulness is fraying at the edges’ are interesting in their own right. While the characters of Zuniga and Moralès remain uniformed, the men’s chorus as a whole are not soldiers and consequently represent a complete cross section of society. After the women emerge from the factory the lighting, courtesy of Alessandro Carletti, suddenly alters as everyone moves in an almost trance like state, thus helping to convey the heady atmosphere of a sun-baked Southern Spain. When Carmen first appears it feels as if the whole town has turned out to see her even more than usual, while the members of the excellent children’s chorus indulge in antics that play out Michieletto’s vision quite literally.

There are, however, some occasions when Michieletto fails to involve the community that are to the detriment of the drama. For example, Act II’s ‘Les tringles des sistres tintaient’ is performed inside the enclosed space, which at this point represents Lillas Pastia’s Inn, with just four people. While it is possible to do so since only three are required to sing, it is hard for the gypsy song to have the same impact without a sense of mass activity that the chorus can provide. Nevertheless, it is clever how Carmen and Escamillo can ‘retire’ to this enclosed space in Act IV and in an instant transform the entire feeling of a stage that had previously been packed with throngs of people anticipating the bullfight.

Aigul Akhmetshina as Carmen in Damiano Michieletto's production of Bizet's Carmen, The Royal Opera ©2025 Marc Brenner

As with the first outing for the production, there remain problems with Michieletto’s thesis, which suggests that when Don José is torn between his traditional small village life and Carmen, it is the draw of his mother and Micaëla that represents his immature side by showing his yearning for security and childish things. It is hard, however, to escape the fact that it is him surrendering everything that he has, or could feasibly have, in pursuit of a relationship that will obviously not last that reveals his immaturity and recklessness. Michieletto’s take suggests that were it not for his mother and Micaëla, Don José might live happily ever after with Carmen, when one could remove those two people from the equation and Carmen’s weariness with Don José by Act III would be completely unchanged.

Michieletto suggests that ‘Every time he could be free, every time there could be a happy end, Micaëla arrives to interrupt it’. It seems odd, however, to turn Micaëla into a disrupting force when she is hardly responsible for Carmen growing tired of Don José, and is actually trying to rescue him from the desperate situation in which he has put himself. In other words, Michieletto’s interpretation fails to acknowledge how his mother and Micaëla serve the function of revealing just how delusional Don José is being. He is not acting as someone who has no other prospects in life, which would mean he was hardly risking anything by pursuing Carmen so single-mindedly, because they offer other options to him.

Nevertheless, Michieletto is right to emphasise how Carmen is a multifaceted person with her own deep needs, and, taken on its own terms, his thesis plays out more effectively now than last year. Carmen’s claims in their Act II duet that she loves Don José, and complaint that he is only too ready to desert her and return to his duties, are usually read as revealing her desire to have what she wants in the moment, showing little care for Don José’s long-term future. However, it is possible to take her words at their face value, and the scene consequently feels very powerful as we feel Carmen meaning every word she says. There are also occasions when Don José’s mother is physically represented, and these generally work well. In the corporal’s first encounter in the opera with Micaëla, her silent presence reminds us of the hold she has over him, and when Carmen deals the card signifying death in Act III her appearance suggests how it is her power over José that will ultimately lead to the gypsy’s demise.

There are other moments, however, that do not work as well. Because everything suggests that at the end of Act III Carmen is urging Don José to leave to see his dying mother because she is tired of him, Carmen is forced to lurch between arguing for his departure and appearing mortified by it to accommodate Michieletto’s thesis. The audience is left not knowing what to feel because it seems too obvious that her reactions are being manufactured to convey two contradictory things that do not fit. It is also hard to reconcile the ending, when Carmen rejects Don José even knowing she may die as a result, with the idea that it is his failure to cast off his family and commit to her that is the barrier to their love, although it is still rendered very powerfully and persuasively in this instance.

Aigul Akhmetshina as Carmen and Freddie De Tommaso as Don José in Damiano Michieletto's production of Bizet's Carmen, The Royal Opera ©2025 Marc Brenner

Aigul Akhmetshina reprises her role of Carmen from the original production, and, while the cast is strong all round, hers remains the standout performance. In being notably rich and sumptuous, yet also impeccably well shaped and controlled, the quality of her mezzo-soprano ties in with the persona she projects as a whole. Her presence is tangible and yet, as should be the case with the character, it never feels as if she is working too hard to assert it. Such apparent effortlessness reveals itself throughout, but especially in the moment when she sings ‘Tralalalala’ to the officers. Although it constitutes an act of defiance, there is little sense in which she has to muster up the courage to assert herself because it feels such a natural thing for her to do.

Compared with Akhmetshina’s Carmen, Freddie De Tommaso’s portrayal of Don José does not feel quite as nuanced, but his committed performance in which his formidable tenor is shown at its most impassioned is extremely stirring. Yaritza Véliz is quite a revelation as her strong and shining soprano conveys both Micaëla’s basic timidity and the courage she finds to enter a smugglers’ den to rescue the man she truly loves. Łukasz Goliński is an effective Escamillo, with his baritone proving secure and robust, although he could afford to assert his presence just a little more in ‘Votre toast, je peux vous le rendre’. There are also some excellent performances from the supporting cast including Marianna Hovanisyan as Frasquita and Jingwen Cai as Mercédès.

In the pit, Sir Mark Elder achieves high levels of precision so that the orchestral playing is always tight, and the balance across the forces as a whole strong. Nevertheless, this is sometimes to the detriment of him capturing the sweeping nature of the music, with the consequence that certain sections, particularly in Acts I and II, do not achieve the required sense of exuberance. The performances from 11 June onwards feature a largely different cast comprising Anna Goryachova as Carmen, Charles Castronovo as Don José, Selene Zanetti as Micaëla and Christian Van Horn as Escamillo, while Ariane Matiakh conducts.

By Sam Smith

Carmen | 9 April - 3 July 2025 | Royal Ballet and Opera, Covent Garden

the 11 of April, 2025 | Print

Comments