© Monika Rittershaus

© Monika Rittershaus

Das Rheingold is the first opera in Richard Wagner’s tetralogy Der Ring des Nibelungen or Ring Cycle. It sets in motion the story that plays out across the four operas, and establishes the central theme of power versus love. It sees the dwarf, or Nibelung, Alberich steal the gold that is guarded by the Rhinemaidens and forge it into a ring that makes the bearer all powerful. He is only able to do so, however, by renouncing love, which in the world we see before us no one has ever done before.

Meanwhile, the chief god Wotan faces his own crisis as he commissioned the giants Fasolt and Fafner to build Valhalla, a fortress that was supposed to put a seal on his supremacy over the whole world. However, in payment he promised them his wife’s sister Freia, which is not only morally reprehensible, but creates a tangible problem as Wotan cannot afford to lose her since she tends the golden apples that keep the gods eternally youthful.

On hearing that Alberich possesses this all powerful ring, the giants agree to relinquish Freia if Wotan can give them that instead. This leads Wotan and his ‘adviser’, the demigod Loge, to descend to Nibelheim, the realm of the Nibelungen, where they discover that Alberich has used the ring’s power to enslave the rest of his race into mining gold for him. Through cunning they succeed in capturing him, with the price of his freedom being the ring. Alberich thus gives it up, but in the process curses the object so it will bring misery and death to those who possess it, and consume those who desire it with an insatiable envy.

Wotan still faces multiple problems because the right thing, as Loge points out, would be to return the ring to the Rhinemaidens, but he cannot do that if he is to relinquish Freia and he also wants to keep it for himself. The earth goddess Erda then appears and advises him to give it up, saying she foresees the end of the gods. Wotan consequently gives the ring to the giants, and Fafner promptly kills Fasolt in order to possess it, thus proving Alberich’s curse is all too real. Wotan has, however, paid his debt and so the end of the opera does see the gods ascend to Valhalla, though they have left a trail of destruction in their wake that, even at this stage, it seems obvious will come back to bite them.

Das Rheingold, Royal Opera House 2023 (c) Monika Rittershaus

This season marks the start of Barrie Kosky’s new Ring Cycle for the Royal Opera, with the plan being to introduce each of the operas individually over the coming years, and then to present them altogether. Kosky’s intention is to make the Mother Earth figure Erda, who normally only appears for one scene in two of the operas, a central figure throughout the Cycle, with the story playing out as her dreams, hallucinations and visions. It is a strong concept as it stresses how stealing the ring equates to raping the earth, highlights the conflict between nature and society in the piece, and brings into focus contemporary concerns regarding environmental catastrophe. However, when it comes to the execution some difficulties creep in, and, while the production is strong on detail, not all of the points it makes entirely work.

The stage is dominated by an enormous ash tree, courtesy of designer Rufus Didwiszus, which lies withered and half fallen since Wotan hacked at it to make his spear. This object equally represents the Rhine, the mountain outside Valhalla where the gods gather, and the Nibelungen’s underground realm of Nibelheim. It proves to be a versatile prop as the Rhinemaidens (superbly sung by Katharina Konradi, Niamh O’Sullivan and Marvic Monreal) pop out of holes in its trunk, and Alberich disappears inside it to execute his various transformations. It also takes on different forms throughout the evening. The gods cover it with a huge, garish picnic blanket as if trying to control, and hence conquer, nature, and when Alberich mines gold in Nibelheim the tree is strapped together with a metal support as the gold pours out of it. With Erda being placed in the tree at this point, having her life force sucked out of her, this shows how the Nibelung is raping nature in his pursuit of wealth and power. Throughout the opera gold is shown in liquid form as if tree sap, a symbol of life and wholesomeness, has now been harnessed for power and greed.

Erda is played by 82-year old Rose Knox-Peebles, and occupies the stage throughout the evening, and most of the time naked, as she observes the action. She sometimes revolves slowly on the spot, and frequently puts her head in her hands, as if conjuring up her next vision while also despairing at the thought of what is happening. She is frequently active in the plot as she sings (or rather mouths) ‘Heia jaheia!’ with the Rhinemaidens, suggesting it is a song she taught them many years ago, and vainly tries to cling to the gold when Alberich steals it. At the point at which Erda normally appears to give Wotan advice, Knox-Peebles spins with, and embraces, him while the earth goddess’s voice (beautifully delivered by Wiebke Lehmkuhl) comes from offstage.

However, although this Erda does important things at key moments, there are lengthy periods when she stands around doing very little, which creates difficulties. Her movements may be slow, but even the presence of a further individual can be distracting by pulling the drama and interactions in one more direction than is necessary. Nothing engages us more than believing that what we see is genuinely occurring before our very eyes. Our ability to connect with the action is thus undermined by the presence of an observer who literally tells us that this is a story to be watched, and the overall suggestion that we are not so much witnessing real events in the here and now as Erda’s dreams.

Overall, having Erda present during the whole of Das Rheingold does work, and chiefly because there is a great skill in being a silent presence that Knox-Peebles certainly possesses. However, if Kosky’s aim is to make Erda present throughout the entire Ring Cycle, one hopes that he finds other (perhaps more metaphorical) ways of ensuring that she is in the other three operas, as a device that is already a little wearing in the first two and a half hours could become far more so over the next twelve. The attempts to make her relevant at each moment are likely to become increasingly obvious, and in the second opera Die Walküre there are many intimate scenes between two characters where even just the presence of a third will disrupt the connection between them. There will also be practical problems since in the third opera Siegfried it will not make sense for Wotan to tell Erda what he did to their daughter Brünnhilde if she was already there to witness it.

Das Rheingold is a difficult piece to stage because it entails ascents to the mountain outside Valhalla, and descents to Nibelheim, and there are no intervals in which scene changes can occur. One cannot therefore blame Kosky for keeping things simple by merely dropping the curtain in between each scene, so that all necessary alterations and manoeuvres can occur behind it. It still, however, feels like something of a cop out since the music in each instance suggests movement or a journey that ought to be replicated in the staging. This said, Alessandro Carletti’s illumination of the proscenium arch every time the curtain falls, so that the gold on it shines bright, is a nice touch. This is also a production that assumes some knowledge of the opera because, for those who lack any, it is unlikely to be obvious from just the words Alberich sings that he transforms into a huge dragon and then a tiny toad who is caught, when the former is no bigger than he is and the latter merely represented by a hand that is then grabbed.

Das Rheingold, Royal Opera House 2023 (c) Monika Rittershaus

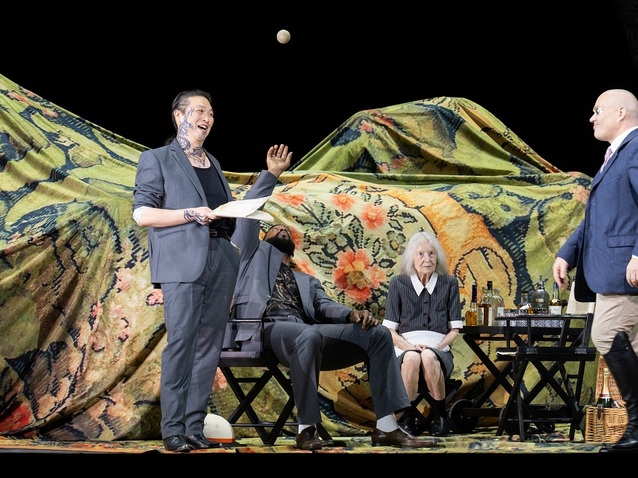

The gods are dressed in polo gear, courtesy of costume designer Victoria Behr, and eat alfresco on the mountain outside Valhalla as they wait for events to unfold. The picnic they have may be a slight nod to Glyndebourne, where Kosky has directed many productions, and overall, with them changing into evening wear for their ascent to Valhalla, the choice works well. It suggests that the gods represent an old Bourgeoisie, who have grown ‘fat’ and ostentatious, while ignoring the fact they have fallen behind the times and are thus facing their end.

What works less well is to dress the giants in such a way as to suggest they are a new trendy middle class who are totally with the times. This is because the giants really are the dying breed, who have been reduced to two in number and who built Valhalla in a desperate attempt to retain relevance by depriving the gods of Freia (a persuasive Kiandra Howarth). It works to dress Fafner in this way, as it reveals his aspirations, but not Fasolt. True, his clothes are not quite as slick as Fafner’s, but they are still similar enough to prevent Fasolt’s essence as an honest artisan, and the real gulf between the two giants’ characters, from being revealed to the full.

There is a lot of detail in the interactions, but while some really help to mark out character, others actually befuddle it by not being the appropriate action for the occasion. When Fafner appears at the gods’ picnic he pours himself a drink without being invited to do so. This reveals his soft attempts to assert power in the situation, and it stands to reason that Wotan would not challenge his rudeness when he is in such a weak position. However, when Fafner’s later questioning of Loge on the nature of the Rhinegold turns into a cake stealing battle no similar purpose is served. Introducing ‘every day’ actions is good when these remain realistic within the context, but, irrespective of the setting, the issue being discussed would be so important to Fafner that he would want to concentrate solely on that. Nor does the manner in which Loge goes about taking them tie in with the idea that this is a deliberate act of distraction from the big issue on the trickster’s part.

It is clever to see Freia serving her apples at the picnic, with Fafner brutally crushing one and Loge holding another back to give to Wotan to sustain him on his journey to Nibelheim. The latter action is a particularly thoughtful touch as normally it stretches credulity that the moment Freia leaves he grows markedly weaker, yet then manages to fulfil an arduous journey. However, because we are encouraged to look in this level of detail, we also notice such flaws as Fafner carrying away the buckets of gold he has gained, even though these are empty because the gold was poured into a bath to cover Freia, and never retrieved from there. The rainbow bridge at the end is beautifully rendered, but it is a slight shame that it seems very similar to that created by Richard Jones in his version for English National Opera in February. As all productions are years in the planning, this is a case of coincidence rather than plagiarism, but having seen the effect before does take the top off what is undoubtedly a wonderful way to portray the bridge.

Sir Antonio Pappano’s conducting is masterly, and, with him having conducted Keith Warner’s Ring Cycle on many occasions over the past nineteen years at the Royal Opera House, it is interesting to see what new insights he brings to the score on this occasion. Christopher Maltman, with his commanding baritone, is a superb Wotan who manages to retain a certain god-like presence and aloofness, despite revealing the full extent to which the character is weighed down by his difficulties. As Alberich, Christopher Purves, with his own arresting baritone, proves to be Wotan’s perfect nemesis, precisely by suggesting that the two figures are ultimately cut from the same cloth.

Sean Panikkar is a first rate Loge, asserting both his tenor instrument and the persona of the smooth trickster to great effect. If the costumes do not help to highlight the contrast between the characters of Fasolt and Fafner, the splendid performances of In Sung Sim and Soloman Howard as the giants certainly do. Marina Prudenskaya, with her strong mezzo-soprano, is a suitably expectant and demanding Fricka, while there is excellent support from Kostas Smoriginas as Donner, Rodrick Dixon as Froh and Brenton Ryan as Mime.

By Sam Smith

Das Rheingold | 11 - 29 September 2023 | Royal Opera House, Covent Garden

the 14 of September, 2023 | Print

Comments