© Stephen Cummiskey

© Stephen Cummiskey

Originally set in Naples, Mozart’s Così fan tutte of 1790 sees the philosopher Don Alfonso challenge two soldiers, Ferrando and Guglielmo, to prove that their respective fiancées, the sisters Dorabella and Fiordiligi, are faithful. He is certain that no woman ever is, but the younger men are so convinced of their own lovers’ fidelity that they agree to a wager with him. They will pretend to be called away to war and then return disguised as Albanians to try to win over the women, and they consent to doing exactly as Don Alfonso instructs over the following day.

Part of the tension lies in the fact that, on the surface, Ferrando and Guglielmo do not wish to succeed in chatting up the sisters because this would prove what they wish to be the case, and win them the bet. However, especially since as strangers they are attempting to woo each others’ lovers, their desire to think they have the ability to win over any woman takes hold, which means that they start to try increasingly hard. Both women do capitulate, but just when the men are despairing and thinking there is no way they could marry them now, Don Alfonso proclaims that that is how all women are and that this should be accepted and celebrated. As a result, the opera usually has a happy ending, although it is a directorial choice whether to restore the lovers to their original couples or keep them with their newly formed ones. In addition, many productions today do opt for less cheerful conclusions so that, for example, all of the characters exit in different directions, suggesting that there was never real love between any of them in the first place.

Serena Malfi as Dorabella ; © ROH 2019.

Photographed by Stephen Cummiskey

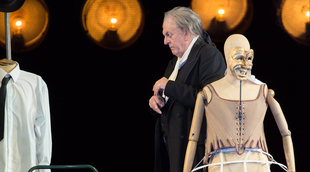

Gyula Orendt as Guglielmo, Thomas Allen as Don Alfonso, Paolo Fanale

as Ferrando ; © ROH 2019. Photographed by Stephen Cummiskey

Così fan tutte is the third and final opera (after Le nozze di Figaro and Don Giovanni) on which Mozart collaborated with the librettist Lorenzo Da Ponte, although in this instance Da Ponte may well have originally written the libretto not for him, but for Vienna’s Court Composer at the time, Antonio Salieri. The pair had had great success with the second version of Salieri’s La scuola de’ gelosi in 1783, and, although the two operas do not involve the same characters, it seems that they were attempting to cash in on its success by producing what they could publicise as a ‘follow-up’ entitled La scuola degli amanti (which is now the subtitle of Così fan tutte). Only it seems after Salieri lost faith in the idea, with no more than a few sketches for two trios in his hand surviving today, did Mozart take it on.

Styles of production for Così fan tutte tend to come in waves. For a long time, many were set in the modern day and this approach was epitomised by Jonathan Miller’s erstwhile version for the Royal Opera, which included mobile phones, laptops and Starbucks coffees. However, while such items felt highly novel in 1995 when it premiered, by the time of the final revival in 2012 they had been seen a thousand times before in operas, meaning that even updates to the modern day were starting to feel tired.

In response, many new productions have opted for another approach, which is to set the drama in a fantasy realm, with the premise being that that is what the opera essentially thrusts the quartet of lovers into as they go on an extraordinary adventure. Phelim McDermott took this approach in his 2014 version for English National Opera, in which he set the action on Coney Island in the 1950s. Meanwhile, Jan Philipp Gloger’s production, first seen at the Royal Opera House in 2016 and now revived by Julia Burbach, uses the setting of a theatre, which offers even more opportunities for Don Alfonso to ‘conjure up’ effects and hence engineer events.

The Overture is accompanied by the six principals appearing in eighteenth century costume and introducing themselves in turn by bowing in a style that befits the character of each. Don Alfonso directs everyone to move and turn appropriately, and it makes us initially think that we will witness a traditional staging in which eighteenth century etiquette and behaviours will play a key role. As soon as it is ended, however, we realise that the quartet of lovers are actually the people who were sitting in a real box (those in eighteenth century costume were simply doubles), and who now clamber onto the stage to put themselves centre-stage in this theatrical set-up.

Continuing in this vein, after Don Alfonso breaks the news to the women that the men are to go off to war, a station, complete with train ready to depart and hoards of other people saying farewell to loved ones, is revealed. The point that this is a theatrical set is emphasised by the fact that as the women turn their backs Don Alfonso (who remains in the same eighteenth century costume for most of the evening) reveals the crowds of parting lovers to be extras by signalling that they can break their poses. Throughout we see him chatting with stage hands as he plans the next effects with them, and the fluidity and slickness of direction are commendable. It means that Don Alfonso can be on or off the stage in a second, leading him to be present for moments when he might not normally be, and absent from others where he usually would, as he goes about moving everything forward.

The difficulty is that to feel for the characters we must be convinced that the women really do believe that their lovers are going to war and are at heartbroken at the prospect, and it is difficult to accept this when they are suddenly transported to a clichéd station platform. This does not mean that stagings can never be metaphorical or symbolic, but there comes a point when the emphasis placed on magic and artifice becomes a severe barrier to us feeling anything for the characters as real people with genuine emotions.

Gyula Orendt as Guglielmo, Serena Malfi as Dorabella, Salome Jicia as

Fiordiligi ; © ROH 2019. Photographed by Stephen Cummiskey

On its own, the station scene might just be believable precisely because Don Alfonso has planned it with the extras to look authentic. As we go deeper into the drama, however, we are presented with a whole series of areas including dressing rooms, costume departments, bars and two theatre sets depicting gardens. Each is designed (by Ben Baur) to make a new point concerning either relationships or artifice (one set depicts Eden suggesting temptation, the other presents a ‘purer’ Arcadian vision), but by the end we are so steeped in the metaphors and commentaries that we have lost sight of the people at the heart of the drama.

That said, this revival has seen some revisions to the staging that have sharpened a few ideas up. For example, last time the four lovers entered via the auditorium clutching real red programmes for this production, but here the act of having them come out of, and return at the end to, the same box makes the ending feel far less as if ambiguity has been introduced for ambiguity’s sake. The message might be something along the lines of ‘be careful what you wish for’. Do we not all, in a sense, go to the theatre to escape from our own worlds, and dream about living the more exciting lives of those we see upon the stage? In this instance, the four have been given the chance to do just that and they must return to their own realm at the end, picking up the pieces from a dream that they realise is not all it is cracked up to be.

In addition, a lot of the ideas that worked well before do so again, while many of the images created by the direction are visually arresting and often extremely measured. For all of the humour to be found in the opera, Così is predominantly about six people, and Gloger’s direction often works well with the fact that much of the piece is played out in arias and intimate moments. One particularly successful scene is that in which Ferrando successfully woos Fiordiligi. This is because here we really do believe that the two when they meet are overcome with sadness, and that their coming together is a reaction to this rather than the product of a preconceived plan for revenge. The fact that the set changes at the end of the scene so that Fiordiligi disappears and Ferrando is suddenly left alone is also clever as we can almost see him thinking to himself ‘did that really just happen?’.

Thomas Allen as Don Alfonso ; © ROH 2019. Photographed by Stephen Cummiskey

Nevertheless, there still remains a problem in the way in which the character of Despina is presented. In the original she is a maid to the sisters, which not only makes her subservient to them, but also means that she knows a wealth of their private details. Here she is a simply a creative type, involved it would seem with costume and set design. The only allusion to her being a maid is that she is first introduced as a barmaid at the theatre’s watering hole (presumably trying to earn some extra money) but even here there is nothing to reveal that the sisters have any hold over her.

Stefano Montanari conducts well on his Royal Opera debut, while the cast pits the superb Sir Thomas Allen, who is an extremely experienced Don Alfonso, against ‘five young operatic talents’. Salome Jicia and Serena Malfi contrast the characters of Fiordiligi and Dorabella very well, while Paolo Fanale brings an excellent combination of expansiveness and lightness to Ferrando’s ‘Un’aura amorosa’ and Gyula Orendt proves a superb actor and brilliant all-rounder as Guglielmo. The highest accolades, however, go to Serena Gamberoni who can in no way be blamed for the misjudgment in the way in which the production establishes the character of Despina, and who thoroughly commands the stage at every turn.

This Così fan tutte still has its share of strengths and weaknesses, but there are undoubtedly many good ideas contained within it. One particularly clever move concerns the way in which late on an illuminated sign reading ‘COSI FAN TUTTE’ has a few lights extinguished to read ‘COSI FAN TUTTI’, thus expressing the phrase in the masculine. This sums up Mozart and Da Ponte’s intentions perfectly because surely they were deliberately presenting the male perspective that ‘women are all the same’, and leaving us to infer from what we saw that men are too!

By Sam Smith

Così fan tutte | 25 February – 16 March 2019 | Royal Opera House, Covent Garden

the 28 of February, 2019 | Print

Comments