© DR

© DR

Polish composer Karol Szymanowski’s Król Roger (King Roger) is by any measure an operatic rarity. Written between 1918 and 1924, and enjoying a handful of outings until 1949, it was entirely neglected for the following twenty-six years. It has experienced something of a renaissance since 1975, when conductor Charles Mackerras led a performance with the New Opera Company in London, but Kasper Holten’s production still marks the first time that it has ever had an outing at the Royal Opera House.

Król Roger tells the story of King Roger II of Sicily whose religious convictions, and by extension powers, are challenged by a humble Shepherd who attempts to win everyone over to his own philosophy. Roger, however, remains steadfast in his Christian beliefs even though his wife Roxana and the people all convert to the easy, hedonistic life advocated by the Shepherd.

The idea that Christianity represents the true, though far from easy, path is explored in many an opera including Poliuto and Les Martyrs by Donizetti and Verdi’s Alzira. Król Roger nevertheless feels unique for several reasons. It was only late on in the composition process that Szymanowski and his co-librettist Jarosław Iwaszkiewicz decided to see Roger resist conversion, and structurally the piece remains interesting. With its three thirty-minute acts described respectively as Byzantine, Oriental and Hellenic, the opera’s themes and music take the audience on a notably varied journey. For example, the evening begins in stunning fashion with the type of chanting associated with the Orthodox tradition.

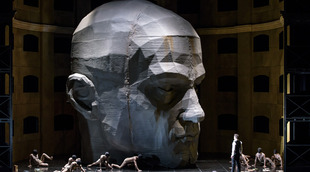

In Holten’s production the original twelfth century setting is sacrificed to place the drama broadly in the twentieth. The stage is surrounded by an arena-like structure that could recall an ancient colosseum, the interior of a Byzantine church or the auditorium of an opera house. Within this lies a giant head that although inanimate still feels capable of expression as different projections cast it in a variety of lights. On some occasions it sports monochrome shades, while on others its lips, eyes and mouth are accentuated. When volcanic oranges appear on the forehead it seems as if we are peering inside the figure’s mind and soul, while lights above and slightly behind the bust see an arrow-like shadow cast before it on the stage.

In Act II the head spins around so that we see ‘inside’ it as the brain is portrayed through a series of floors connected by staircases. The books that this area contains allude to knowledge, while bright lights double as eyes. In one sense, the head could be a metaphor for religion itself. Looked at from the front it presents a beauteous ideal that could only come it seems from an ethereal realm. Behind the façade, however, there is a mind at work (in the form of Roger’s government) that has to put time and energy into projecting such an image.

Although the production is for the most part successful, Act II’s ecstatic dance in which the Shepherd tempts Roxana and the people is less effective than it should be. The dancers here are hooded, dirtied figures who it is hard to believe would be enticing at all. The Shepherd sings that he refuses to be a slave to the King, and so they surely represent vassals rebelling. This, however, is an instance in which it is not enough to understand the point behind an idea. We need to be able to feel the allure for ourselves.

The short third act does not benefit from being separated from the other two by an interval. Given the logistics of the staging it may have been impossible to run the opera without pause, but with Act III on its own feeling slight, it does make the close of the evening seem a little insubstantial. This is compounded by the fact that the same arena for the action is maintained throughout. Even though it is the third act that traditionally takes place in a Greek theatre, the lack of variation in setting diminishes the sense of progression from start to finish. The difficulties, however, are largely mollified by the outstanding performance of Mariusz Kwiecień as Roger whose baritone voice is smooth, precise and powerful. On opening night the audience was warned that he was feeling a little under the weather, but it did not show for a second.

Saimir Pirgu takes a little time to warm up as the Shepherd leading to a few moments that feel strained and unfocussed, but overall he delivers an excellent performance as his tenor voice can be exceedingly light or immensely powerful at the top of its register. Pirgu, who played the Duke of Mantua in Rigoletto at the Royal Opera House last September, is still relatively young at 33 and could become one of the world’s great tenors.

Georgia Jarman produces the most mesmerising, beautiful and spiritual sound as Roxana, Kim Begley is strong as Roger’s loyal advisor Edrisi, while the conducting of Royal Opera Music Director Antonio Pappano is focussed and precise.

The chances to experience Król Roger, at least fully staged, are few and far between. Given the overwhelming strength of this cast and the considerable merits of Holten’s production, the current opportunity should be seized at all costs.

By Sam Smith

Król Roger | 1 – 19 May 2015 | Royal Opera House, Covent Garden

the 03 of May, 2015 | Print

Comments