© (c) Catherine Ashmore

© (c) Catherine Ashmore

Despite only being mentioned briefly in the New Testament, the character of Salome has certainly caught the imagination as she has pervaded art, literature and music over the centuries. In the Gospels of Matthew and Mark she is described as a girl who pleased King Herod so much at his birthday feast with her dancing that he promised her anything she desired. After consulting Herodias, the husband of Herod and her mother, she asked for the head of John the Baptist on a plate, with Herodias desiring this because John had proclaimed her marriage to be unlawful. The King was mortified, but could not go back on a promise he had made in front of so many guests and so ordered John’s execution.

So brief is the girl’s appearance in the Bible that she is not even named, being referred to simply as the daughter of Herodias. She was subsequently given the name of Salome, however, after being linked to the eponymous figure who was mentioned as a stepdaughter of Herod Antipas in Josephus’ Jewish Antiquities. Subsequent depictions have tended to present her as an icon of dangerous female seductiveness, with her entertainment having acquired the title of the Dance of the Seven Veils. Some, however, have identified her light-hearted and cold foolishness as the trait that led to John the Baptist’s death. Oscar Wilde’s Symbolist play, which premiered in Paris in 1896, sees Salome take a perverse fancy to John, and insist on his execution when he spurns her affections. It is this version of events that Richard Strauss, working from Hedwig Lachmann’s German translation of the Wilde, largely follows in his opera of 1905 as he includes her kissing the severed head at the end.

Adena Jacobs’ offering for English National Opera is advertised as a ‘radical new production exploring a princess suffocated by a brutal masculine world’. The difficulty is that this is what the opera is about anyway, and so taking additional steps to emphasise certain points that should really be allowed to bubble beneath the surface throws the piece off balance.

For example, Jokanaan (John the Baptist) shuns Salome as a temptress, blaming her for the ‘sins’ of her mother and all women since the fall of Eve. As a result, and especially in the modern day, it is easy to see why he could be classed as misogynistic. However, any attempt to emphasise this aspect of his character, even just a little more than usual, makes Jokanaan start to feel like a man who is almost as bad as any other in the story. This is a problem because his godliness, which makes Herod both revere and fear him and the Jewish authorities want to control him, has to stand in absolute contrast to any other character. In fact, in this presentation the idea that the Jewish authorities wield considerable power that Herod has to contend with does not register at all.

The story is told broadly in the modern day so that it begins in some kind of club. However, there is no really strong setting, which in reality makes the action seem rather devoid of context. When this is coupled with points that do not flow particularly naturally from the original, it makes it harder at least to feel for what unfolds.

The interactions in Salome’s key encounter with Jokanaan as a prisoner always have to be managed carefully because she is enraptured with him, while he repels her advances. However, the set-up here affects the chemistry by having them apart for the majority of the scene, so that they could almost be in different rooms. As a result, for all of the physical actions that she carries out to show it, we do not feel the intensity of Salome’s passion for Jokanaan for ourselves, which makes it hard to appreciate why she subsequently behaves as she does. This Jokanaan wears high heels, which seems to be an attempt for a production that has asserted his misogyny in shunning her to create some distance between him and the other men still, but it only muddies the waters further. In addition, a camera strapped to the front of his head films his moving lips as he sings, with the images projected live onto the set. This may emphasise the idea that his are the words of a prophet, or draw our attention to Salome’s lust for his lips, but there are simpler and more effective ways of making us feel this for ourselves.

Even the final scene when Salome is presented with, and clutches, Jokanaan’s head in a bag is affected by this far earlier one. Our inability to grasp the strength of her feelings for Jokanaan before makes it difficult to sense them now, and nor does the production seem that intent on wanting to make us feel them. While Salome normally sings directly to Jokanaan’s head, here it comes in a bag and she soon places it on the floor as Herodias embraces her from behind, even having a gun ready before Herod has given the order to kill her. The focus to the end is on the women, but to downplay Salome’s relationship with Jokanaan, and to emphasise Herodias’s role by handing her actions that hardly make sense, undermines too much of the story. There are, however, some interesting touches so that a slain and skinned beast being prepared for eating has innards that look like flowers. Salome then references these when Herod tries to dissuade her from asking for Jokanaan’s head by saying that it would be such an awful sight for her to see.

The orchestral playing, under the baton of Martyn Brabbins, is both powerful and precise, but its impact can be thwarted by what is happening on stage. There are moments when everything does work together so that the most bracing music is accompanied visually by a man ducking a woman’s head under water and others knifing the beast’s carcass. However, the Dance of the Seven Veils feels lame as Salome adopts a series of seductive poses that a model might execute in a modern day photo shoot before four dancers take over.

It is not necessary for Salome actually to become naked, and getting trained dancers to carry out much of the movement might seem sensible. However, Salome’s movements are too quiet when she is centre-stage, and then she has the focus taken away from her so much that her allure does not register anywhere near as strongly as it should. Nevertheless, it is telling that she becomes (semi-)naked when she confronts Jokanaan as if she really wishes to bear herself to him, but not when she is merely putting on an act to get what she wants from someone for whom she has no feelings.

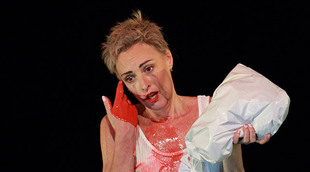

The cast is generally strong, with the majority of any weaknesses that they show deriving from how the production requires them to behave. Allison Cook, blessed with a pleasing mezzo-soprano (the role is more normally taken by a soprano), has a certain allure as Salome, and it is a shame that the production does not allow her to focus this and her passions more towards those things that would really move us. David Soar’s bass may be heard to better effect when he is onstage rather than amplified from off it, but it is tremendously rich, dark and powerful. One wishes that Michael Colvin had been allowed to bring a degree more gravitas to the role of Herod as his assertions of power and desperation are all played out with a dose of frenetic comedy, but there is no denying that, with his excellent tenor, he can fill a stage. Stuart Jackson stands out in the relatively small role of Narraboth, while Susan Bickley is simply a class act as Herodias.

By Sam Smith

Salome | 28 September – 23 October 2018 | London Coliseum

the 01 of October, 2018 | Print

Comments