© Gran Teatre del Liceu 2025 (c) David Ruano

© Gran Teatre del Liceu 2025 (c) David Ruano

Thomas Mann, in one of the most famous cases of audio-visual synaesthesia, stated in a letter to visual artist Emil Pretorius that Lohengrin’s sound is ‘silvery blue’. It may be so. Josep Pons, the great triumph of the premiere night achieved Lohengrin’s beautiful silvery blue sound.

Pons, the principal conductor at Liceu’s Orchestra since 2012, achieved with this Lohengrin one of the best performances of the orchestra in the last few seasons. The ensemble sounded splendidly from the initial prelude, when the divisi in the violins offered a magical music which seemed to dawn on the audience from a different dimension, from a different world less miserable than ours. The orchestra sounded darkly menacing in the prelude to the second act and bright and energised in the prelude to the third. Brass, woodwinds, every party played with precision, nuances and in delicate balance with the strings. The attentive concertation between the pit and the stage allowed the orchestra to keep its character whilst allowing the voices to get through with ease. Pons will be leaving his role as principal conductor at Liceu at the end of the 25-26 season – he will be missed. The choir, with plenty to do in Lohengrin, was also sensational and offered without a doubt the best performance of the season.

Lohengrin, Gran Teatre del Liceu 2025 (c) David Ruano

The soloists’ section, almost all regulars at the Bayreuth Festival, also contributed notably to the silvery blue sound. Klaus Florian Vogt, with his long Wagnerian experience, possesses an unusually clear and light voice which sets him aside from the traditional vocal colour of the typical Wagnerian tenor. In the most epic passages, perhaps it would have been ideal to offer a voice with greater body and a denser colour. In the lyrical passages however, Vogt was a lot more convincing, and his impeccable technique allowed him to fill the performance with exquisite nuances.

Elisabeth Teige, debuting at the theatre, didn’t offer an anthological Elsa but was totally sufficient. Most importantly, she steadily improved throughout the performance. The young voice, which is now lyrical and will probably become more dramatic with time, allowed her to bring an appropriately sweet Elsa, well suited to the score.

Miina-Liisa Värelä, who had already sung in Ariadne auf Naxos at Liceu, excelled musically, scenically and in all areas in the demanding and complex role of Ortrud. The Finish soprano seems to be an ideal singer for this difficult character. With a fully robust dramatic soprano voice, she offers power, force and an impressive vocal presence.

It was initially planned for Irene Theorin to sing Ortrud, but as a result of serious “artistic discrepancies”, euphemism that the theatre has used to express the profound feud between the Swedish soprano and the stage director, Theorin didn’t take part in the premiere performance where the presence of the stage director is compulsory in the rounds of applause. She will however sing in the five remaining performances. What a strange “artistic discrepancy” that which only affects one out of the six performances. Theorin, highly esteemed at Liceu, will have to offer a great gig to convince the audience that she can outperform her substitute, given how complete, well-rounded and unappealable Miina-Liisa Värelä’s triumph was.

Ólafur Sigurdarson resolved sufficiently but without brilliance the difficult role of Telramund, one of the most unrewarding baritone roles of the Wagnerian repertoire. Telramund is a nobleman, therefore the style needed to be more majestic, it lacked vocal assertiveness. Günther Groissböck did bring authority to the character of king Heinrich, though he struggled to give enough weight and confidence in the demanding lower notes that Wagner wrote for this role. Roman Trekel fulfilled well the herald role.

Lohengrin, Gran Teatre del Liceu 2025 (c) David Ruano

Lohengrin, the opera which with over 200 shows is the most performed Wagner title at Liceu, was presented in a new inhouse production. This Lohengrin, which was due to be premiered in the spring of 2020, was well rehearsed by the time everything was closed down due to the pandemic. Due to logistical issues, it wasn’t possible to feature it in the upcoming seasons and it wasn’t able to be presented in Leipzig in 2022 either. This was therefore, with a five year delay, the world premiere of the new Liceu production signed by Katharina Wagner as stage director, the great-granddaughter of the composer and director of the Bayreuth Festival.

In strictly visual terms, the proposal of this new production isn’t very attractive. A low interest scenography rejects the audience’s gaze rather than attracting and focusing it. An excessively dark lighting at points compromised the understanding of what was happening on stage and the costumes were uninspiring. In terms of the acting, the gestures and physical interaction between characters navigated overly traditional parameters. The choir for example was treated as an anonymous mass which always seemed to be a nuisance on stage.

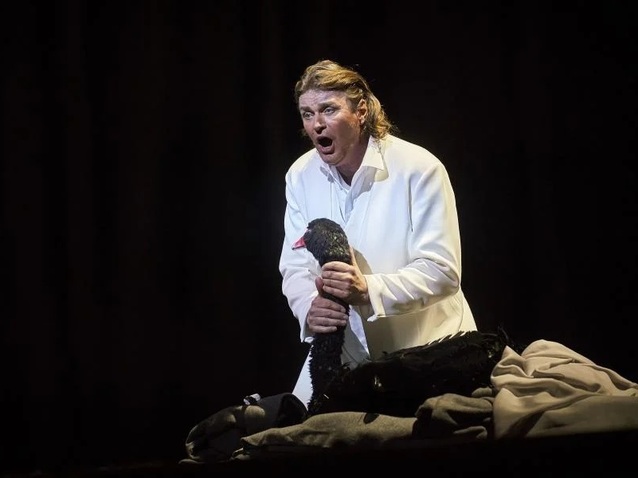

The singularity and personality of the new production lied exclusively in the concept, the intentionality and ultimately in the final meaning of Lohengrin – here is where something was happening. An added imagined mute scene that takes place during the initial prelude shows Lohengrin murdering Gottfried, Elsa’s brother, heir to the duchy of Brabant. A black swan witnesses the crime. This moral reversal that turns the ‘good’ into the ‘evil’ and vice versa is the axis, weak and insufficiently justified, around which the new proposal of Katharina Wagner revolves. A clear case of Regietheater.

The proposal works with great diffulty during the first and second acts, but flounders in the third. Not only does the action on stage betray the text – and most importantly, the music – but the stage director manages to make the narrative totally incomprehensible by introducing a delayed splitting of the feminin characters. The witnessing swan accusingly reappears repeatedly thourghout the opera, becoming the expression of Lohengrin’s paranoia. These appearances become so recurrent that towards the end the swan’s sightings start turning into a kind of ‘where is Wally’ game, for example when we discover him inside Lohengrin’s wardrobe, which brought a slight hilarity to the audience.

In this Lohengrinwhich lacks redemption, a highly important element of the Wagnerian drama, Lohengrin the psychopath ends up stabbing the damned swan whilst singing the celebrated “In fernem Land”.

The final generalised scolding toward the stage direction, only lightly attenuated by some timid applause, will be remembered for a while. Genius isn’t hereditary.

Xavier Pujol

Barcelona, 17th March 2025

Lohengrin by Richard Wagner. Günther Groissböck, bass. Klaus Florian Vogt, tenor. Elisabeth Teige, soprano. Ólafur Sigurdarson, baritone. Miina-Liisa Värelä, soprano. Roman Trekel, baritone. Orchestra of Gran Teatre del Liceu. Choir of Gran Teatre del Liceu. Josep Pons, conductor. Katharina Wagner, stage director. Marc Löhrer, scenography. Thomas Kaiser, costumes. Peter E. Younes, lighting. Production by Gran Teatre del Liceu.

the 19 of March, 2025 | Print

Comments