© DR

© DR

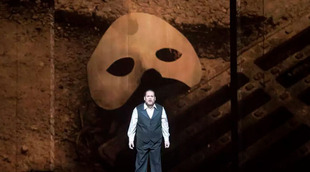

Rigoletto is one of the cornerstones of the repertory of a great opera house like the Paris Opera: you cannot, must not miss it. But at the same time you can’t simply keep repeating conventional images of it. It needs to be part of that ceaselessly shifting movement that still today makes us talk about opera, even in the case of these works from the past. In 1851, Verdi was 38 years old: Rigoletto is thus an opera from his mature period – but most of all it is a work born when Giuseppe Verdi matured as a man, a man for whom fate saved some violent, tragic moments, including the death of his two children, his son Icilio and his daughter Virginia. She died on 12 August 1838, when he was not yet 25 years old: it was clearly a traumatic event, which we can imagine he relieved when he was composing Rigoletto. That is why a curse is of course the apparent common theme that runs through this drama, from the first scene to the end of the opera; the relationship between the father and his daughter, between Rigoletto and Gilda, is even more a hallmark of this tragedy. As it usually does, the staging by Claus Guth sheds new light on this painful perspective. This Rigoletto, who appears during the Prelude, a sort of shunned bum who carries around with him this wretched cardboard box containing the remnants of his life, the relics of his unhappiness, this white bloodstained dress, the dress of Gilda whose congealed blood is as much the blood of her deflowering as of her death, this Rigoletto is also Verdi’s double, the man who had a daughter - and lost her. Starting with this initial, poignant image, everything will unfurl, everything will make sense: what we are going to see is the drama of this man who has lost his daughter in all senses of the word, i.e., who lost her because he did not let her live. On several occasions, this stage double for Rigoletto will attempt to get back in the game, to keep a dire fate from being fulfilled - in vain, of course: you cannot correct time, or go back in time. All that is left is for him to relive the nightmare, to plunge into the dark box of memory. Throughout the performance, Rigoletto will be a silent witness to the tragedy that progresses implacably, which he sees again in a sort of long flashback. For the spectator, no doubt, this set - the open cardboard box, inviting us to plunge right in - may be somewhat austere, but it is highly significant and dynamizes the music, which seems to give flesh to this theatrical skeleton shown on this bare set. This is true especially as the stage directing by Claus Guth is delicate, precise, almost razor-like: everything shows up there, everything is in order, everything makes sense. This is also why audiences will deplore the two or three moments when the director forgets himself, laying it on with props, which becomes pointless, cluttering up some scenes with parasitic characters – as in Gilda’s solitary scene, the “Caro nome” in which she acknowledges the love that is overcoming her, the intense introspection of the girl turning into a woman. Why disturb this powerful moment with the appearance of three dancing girls who are supposed to symbolize the ages of life? Why, nonsensically, bring back the Duke at this point who caresses her insistently? As if, for this scene, Claus Guth no longer trusted the music, or thought the spectator too stupid to listen and understand? Pity! But aside from this bit of incongruous slag, this staging has real power, sustained by a judicious use of video (ah, that lovely, poetic image of the little girl running through the fields towards her destiny), borne along by always relevant intuitions (highlighting the fact that Rigoletto and Sparafucile are twins) and it culminates with a shattering ending – when Gilda dies, no longer 100% realistic but in a poignant reverie that takes her out of the world of her father, to die on her own somehow, leaving him alone, abandoned, holding his daughter’s blood-stained dress.

This theatrical tale would not hold such powwer without the magnificent cast chosen by the Paris Opera. Heading up the cast is the Rigoletto played by Hawaian baritone Quinn Kelsey who presents a rigth and affecting personality supported by a full, warm, fleshy, moving voice - perhaps lacking a bit of dark timbre for “Cortigiani” – constantly carried along by this broken heart he expresses so well. Opposite him, Gilda as played by Olga Peretyatko is superlative: the voice is a perpetual delight; her bel canto art (she has sung a lot of Rossini and Donizetti) enables her to string her notes together gracefully. to colour them without ever weighing them down, to be as precise with pointed sharps as with subtle piano parts – all while playing this delicately crazy character with a touching grace. American tenor Michael Fabiano does not reach that level: the character is well drawn and the voice carries and has an impact, but subtlety is not his forte. This role of the Duke is no longer what suits him today: having expanded his vocal range, he struggles to lighten his voice sufficiently which sometimes leads him to produce a hard, metallic sound. The rest of the cast is excellent – with just one exception, the Bulgarian mezzo Vesselina Kasarova, completely out of place as Maddalena. Audiences will especially like Rafal Siwek’s bass notes; he makes an excellent Sparafucile. Or Mikhaïl Kolelishvili, winner of the Monte Carlo 2008 Singing Masters, as Monterone. But all the roles, even the smallest ones, are beautifully cast: this is the sign of a great opera house. Finally, all this is conducted by the baton of the young and brilliant maestro Nicola Luisotti, who gives off a constant energy, with broken and repeating rhythms that always accentuate the dramnatic power of the show – and contribute to a lovely, overall success, which is what we have a right to expect from a theatre like the Paris Opera.

Alain Duault

Rigoletto at the Paris Opera, April 9th to May 30th

the 20 of April, 2016 | Print

Comments